Walk around the grounds of St Andrew’s Church in Bredfield and what nature do you see: trees and grass; a bee buzzing past; a bird perched in a tree? Anything else? Look closer at the headstones, especially the old ones. Examine the branches of some of the older trees? Something else is there. Indeed, it’s mostly everywhere: on plants, fences, brickwork, stonework and paths. It’s lichen!

In this article, we’re going to have a close look at lichen. I know, it doesn’t sound exiting, but don’t give up now. Lichen is weird, wonderful and an integral part of a healthy ecosystem.

The first weird and wonderful thing about lichen is that it isn’t a single organism. It is made up of three organisms, each from three kingdoms of life: fungi (including yeast), plants (algae) and bacteria These three organisms exist in a mutualistic relationship, though the rewards may not be equally distributed.

The relationships between the three elements are complex and much is yet to be discovered, so here’s a simplified explanation. The fungus element of lichen provides an affixing base and a structure for the plant element. In return for this service, the fungus receives essential carbon nutrients in the form of sugars, produced by the photosynthesis of the plant element and the bacteria. Lichen are fungi that have discovered agriculture!

In some lichens, it is possible to see both the fungus and the plant element. A magnifying glass would help. (You would need a microscope to see the bacteria element!) 98% of all lichen fungi are cup-fungi (known as ‘ascomycetes’) and, if you look closely, you can often see these minute cups. The plant element of the lichen be quite obvious in some lichen: leafy (in ‘foliose’ lichen) or even beard-like (in some ‘fruiticose’ lichen). In the photos below, you can see fungus cups in the lefthand image, algae leaves in the central image, and the fronds of a fruiticose lichen in the righthand image

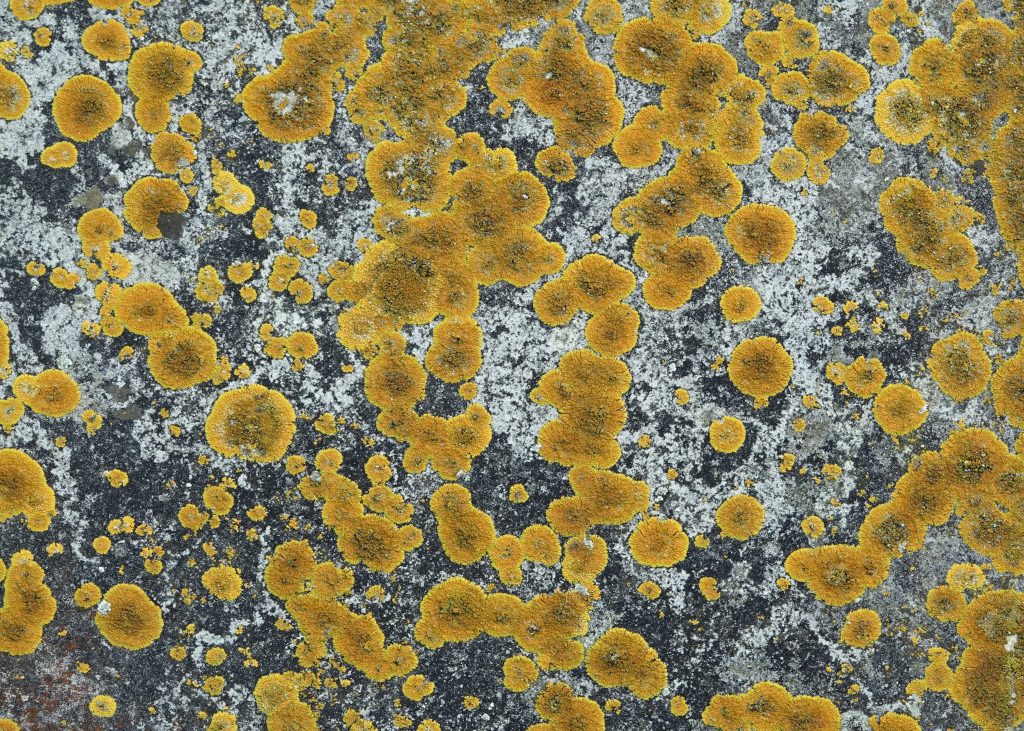

Common Orange Cup – Xanthoria parientina

Common Greenshield – Flavoparmelia caperata

Cartilage Lichen – Ramalina farinacea

Lichens play a crucial role in the ecosystems that they grow in: they release oxygen into the atmosphere; they can provide sustenance (though quite minimal) to some herbivores; they provide shelter for small invertebrates (such as Springtails), which are then sought-out by small birds; they can provide nesting material for birds; they can protect trees from extreme wind, rain and snow; and they can contribute to soil creation by breaking down rocks (though very, very slowly!). The health of lichen growth is an extremely good indicator of air quality. Scientists are currently exploring how lichen may be a source of new medicines.

Several species of moth have a close affinity with lichen. The larvae of several species of moth, including the aptly-named Tree-lichen Beauty, feed on lichen. In a ‘hard-wired’ behaviour, several species of moth will fly to the camouflage of lichen to escape predators.

Green-brindled Crescent moth on Common Organge Cup Lichen

Don’t be misled into thinking that the presence of lichen on a plant has an adverse effect on the plant’s health. It doesn’t. Lichen will continue to flourish on an unhealthy plant or tree, but it doesn’t cause ill-health. Indeed, if you set about removing lichen from a tree, it may create wound sites where plant pathogens could enter and cause real disease symptoms to occur.

Let’s conclude with some amazing facts about lichen: they arrived on earth at least 250 million years ago; they currently cover about 7% of the world’s surface; some churchyards have been found to contain 100 species of lichen; Lecanora muralis (so-called ‘Chewing Gum Lichen’) has colonized that most inhospitable of British environments – supermarket car-parks! Last, but certainly not least, there is an aesthetic beauty in the patterns that lichens create, especially on stone.

Hopefully, you’ll never look at ‘boring’ lichen in the same way again.

If you’re in the mood for a relaxed, mindfulness experience of nature’s patterns, please view our video of the lichen and algae in the churchyard of St Andrew’s.

All photographs taken locally.