Leaf lines and blotches

Come autumn, something starts to happen with our leaves. Not only are they changing colour to rich browns, yellows and reds; they also often show blotches and lines. These blotches and lines are often (though by no means always) signs of life within the leaves. It is difficult for us to conceive, but something is living between the top surface of the leaf and the bottom surface. A leaf looks two-dimensional but, for a tiny insect larva, there’s a third dimension that provides space to take shelter and eat. What is found to eat in there are the sugars that the green chlorophyll pigments produce. Let’s look at life in the leaf.

Miners

When an insect larva lives and eats within the leaf, it’s called ‘mining’ and the larvae are called ‘leaf miners’. Flies and moths are the two main orders of insects than contain leaf-miners. Here we are going to focus on leaf-mining moths; all very tiny ‘micro-moths’. Most of these leaf-mining moths have preferences for a particular type of tree-leaf. The adult moth will lay her eggs on or near the leaves of the preferred tree, and the emerging larvae will subsequently set about their work. Here we will look at the moth larvae miners to be found on three common trees: Apple, Horse Chestnut and Oak. Before we do this, it should be pointed out that the mining done by the larvae doesn’t usually damage the tree or the fruit; though it may look rather ‘unsightly’ to some people.

Apple Leaf Miner

You can see evidence of the Apple Leaf-miner moth (Lyonetia clerkella) quite easily. You’ll find a narrow brown squiggly line running along part of the green Apple leaf (see left-hand image below). That line has been made by the feeding of the moth larva. Below (the right-hand image) is a close up of an Apple leaf. Here the moth larva has travelled from left to right, and the line of brown speckles is the ‘frass’ left after it’s feeding. (‘Frass’ is an entomologist’s euphemism for ‘poo’!). The larva can be seen to the right.

Apple Tree leaf Mine

The larva within the Apple leaf

Horse Chestnut Leaf Miner

Our second leaf-mining moth is the Horse-chestnut Leaf-miner (Cameraria ohridella). At the time of the year when the conkers come, Horse Chestnut leaves can be covered in lots of blotches. Soon after, they begin to turn a lovely yellow and brown and then they fall. The Horse-chestnut Leaf-miner is a fairly recent arrival to Britain; the first example being found in 2014. It has spread rapidly and it may now be difficult to find a Horse Chestnut tree that it doesn’t inhabit. Each species of leaf-miner tends to leave a particular shape of mine in the leaf. Horse-chestnut Leaf-miners tend to leave elongated blotches (see left-hand image below), rather than the squiggly line of the former species. Below (right-hand image) is a close-up of the larva within the leaf: it is clearly evident in the middle of the picture, with the area in which it has been feeding to the left. The adult moth is minute, but it is rather attractive: dark reddish-brown with white-and-black stripes.

Horse Chestnut leaf mines

The larva within the Horse Chestnut leaf

Oak Leaf Miner

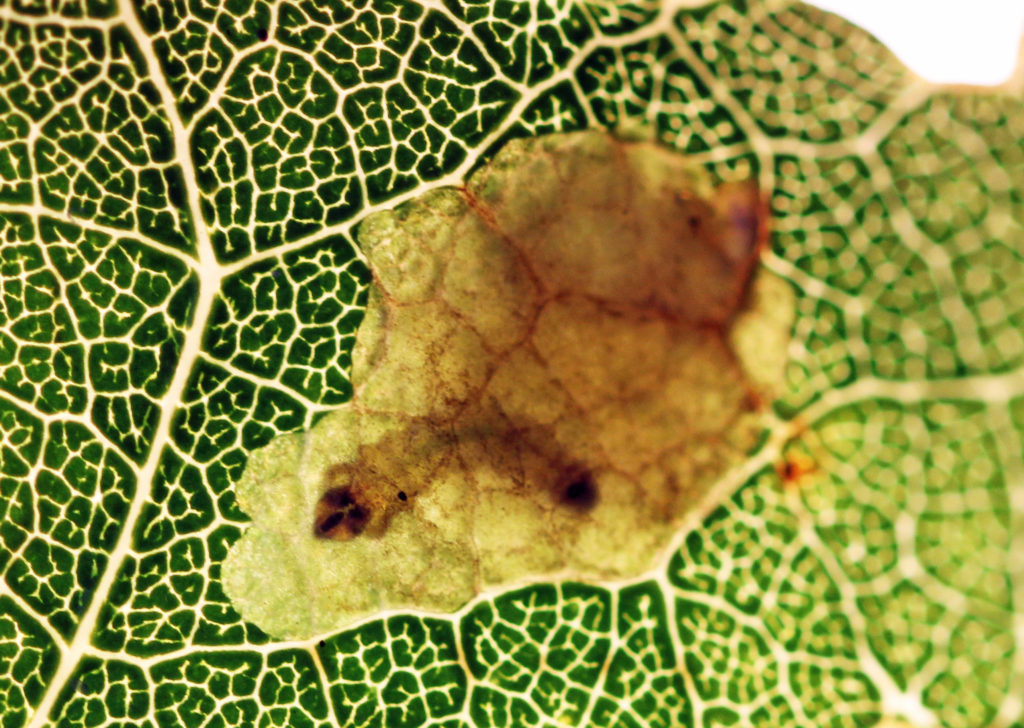

The final leaf-mining moth we’ll look at is the one which is to be found on English Oak trees (Quercus ruber). Its scientific name is Tischeria ekebladella, though it has recently been given a vernacular English name: ‘Oak Carl’. This moth is also a ‘blotcher’, not a creator of squiggly lines. The blotch is evident on the upper-side of the leaf (see left-hand image below) and within it the larva lives and feeds; and creates a silky-type ‘web’. This species is rather more house-proud and ejects its frass through a hole in the leaf. In the right-hand image below, you can see the larva as a boomerang shape, with a dark head and anus.

Oak leaf mine

The larva within the Oak leaf

Leaves in Autumn

In autumn, deciduous trees prepare for the winter and, before falling, their leaves turn those wonderful shades of brown, red and yellow. This is a spectacle for humans to observe, but not a welcome change for the leaf-miners, which are wanting to feed on the sugars produced by the green chlorophyll. However, some leaf-miners have developed a way to get around this problem: they host bacteria that release a chemical, preventing nearby leaf cells from turning brown. (See images below of the Red Hazel Midget – Phyllonorycter nicellii – at work in a fallen Hazel leaf. The green areas can be seen on the upper and the underside of the leaf. The right-hand images shows the moth lavae. This can happen even after the leaf has fallen from the tree. So, if you find a fallen brown leaf with a green patch on it, the chances are you’ve found a leaf-miner still at home.

Phyllonorycter nicellii leaf mine – upperside

Phyllonorycter nicellii leaf mine – underside

Phyllonorycter nicellii larva

Leaving the Leaf

When the leaf-mining larva has developed sufficiently, it will vacate the mine and look for somewhere to pupate – probably in a small web clinging to the underside of the same leaf. After some time, an adult moth will emerge from the pupa. The adult will later lay her eggs on the tree and the cycle begins again. These leaf-mining micro moth are extremely small – somewhere in the region of 4mm in length – so, unfortunately, you are unlikely to ever see them. Here is a picture of an adult Horse-chestnut Leaf-miner (Cameraria ohridella) hiding underneath a Horse-chestnut leaf, soon to begin the next round of egg-laying and leaf-mining larva.

Adult Horse-chestnut Leaf-miner (Cameraria ohridella) hiding beneath Horse-chestnut leaf.

Predators

Life within the leaf is much safer for the larvae than feeding on the outside. Nevertheless, their cover is not impenetrable. Parasitic wasps, such as the Ruby tailed Wasp, are still able to find where the larva is hiding and oviposit eggs within the larva. The clever Blue Tit, which is always quick to learn new tricks, has learnt to search the leaves and extract the larva with its beak.

All the images in this article were taken by Stewart Belfield, in Bredfield, October 2021 and May 2022. For the close-up images of larva, the leaves were back-lit and photographed with a macro lens.